Episodic Ataxia: The Invisible Impairment

Often misdiagnosed, misunderstood, and unseen. A sufferer writes of a silver lining in his tale of swoon and gloom.

by Timothy Wahl

My childhood was the picture of any normal kid. I hopped, skipped, and jumped just like the rest. Then, at age 11, my life turned on its back. Things would not be normal again. A mystery “illness” appeared out of the blue. Nothing started it; it just began. No one had the foggiest idea of what disabled me. Nothing to see, nothing to put a finger on.

“All in your head,” moaned my father, a farmer. He relied on me to help run the dairy business, milking cows, getting in hay, shoveling manure, and all that comes with running a farm. His proclamation made sense. A string of doctors and shot-in-the-dark medical diagnoses drew blanks on what caused my life to become a sweaty hell of periodic prostration from vertigo and its accouterments of imbalance and physical incoordination that to him always seemed to come at the most convenient of times, like when there was work to be done. If this were an act, my performance was worthy of an Oscar.

The episodes first appeared during a softball game in sixth-grade gym class. My turn at the plate and as the pitcher lobbed the ball, I felt a spike of energy, and adrenaline, my muscles tensed. I smacked the ball like Superman, good for a single, at least. Just then, all the wheels on me fell apart. My arms and legs flailed, taking on a mind of their own. I wobbled a step or two out of the batter’s box. The earth didn’t stand still, swirling, closing in, then down, kerplunk, on the dropped bat, on the base path. I was out, not cold, but far from first base.

The journey to find out what ailed me began right after with the kindly village doctor in my home village, Andover, New York. “Say ah,” which I did. Tonsils checked out. So did the rest of me. It must have been a bug, I remember the doctor telling Mom.

It was a bug alright—a bug that set the parameters for how I was to tackle life from then on. Getting sick as a dog, words we used back then, in 1961, was how it was for episodes that came about every two weeks, a drama with the feeling of pestering waves that tossed and turned me hither and thither, sweat seeming like a lava flow while I vomited or dry-heaved. The formula for my recovery was to lie stone still—cold air all around was best—and ride it out, a few minutes if I conked out or an unholy eternity of a few hours if I lay awake. At the storm’s end came tranquility and stillness; the air was clear and my head a blank slate.

Days in-between episodes were off and on with feelings of being spastic, jumpy, and herky-jerky. Picture a fish out of water flopping and thrashing to the breathless end. At times, I wished this to be my fate.

I had mistakenly referred to my bouts as dizzy spells, which got doctors to wrongly zero in on fainting, not vertigo. Whatever, the upshot was my life as a pre-teen with ambitions to play sports was sailing away. I faced relegation to a spectator.

Even that had caveats. Triggers could be excitement from rooting for a team or getting stressed by a tight game. A hot gymnasium and the loudness and ruckus of fellow fans, bouncing balls on hardwood, back and forth, up and down, and buzzers—all this or any combination could make me teeter. Clearly, yipping it up was never more to be.

Physical action was the primary symptom that led to triggers of episodes. I tried not to get sick on days I was needed in the hayfield, but I had no say over such matters. No time was opportune for these whenever, wherever gatecrashers. Bouts could also be sparked by caffeine. Too bad for me—coffee was my beverage, but I still took my chances. Extremes in weather, hot bath water, or merely thinking, worrying, and fretting about a spell could do the trick.

Stress, like standing and delivering before any group, was hazardous. Depending on the circumstance, my speech could become slurred in the vein of Foster Brooks, a comedian of the day whose schtick was playing a drunk. I tended to stutter and grasp for the right words, compounded by a brain that got cloudy. How stupid I felt when good first impressions mattered, like before a panel at a job interview. I did not associate any of this behavior with my “hidden malady;” instead, it was a personality deficit, I figured.

So, as a matter of fact, my “dizzy spells” had become so there was little notice among school mates and teachers when I would have one. Once, an episode nabbed me in a soccer scrimmage during PE. I managed to sneak away from the action and plopped myself down in a batch of quack grass off to the side. Everyone returned to the locker room at the bell with me still a clump in the weeds.

PE included lessons in the school swimming pool, where I fared no better. The water was a little warm for my liking as was the steamy locker room, whose ubiquitous, obnoxious smell of chlorine made me edgy. I never got the hang of moving my arms and legs in tandem. My best and only “stroke” was the dead man’s float. One day, impish classmates must have thought they were being clever. They were to teach me to swim the old-fashioned way, a sink-or-swim heave-ho into the deep end. This method proved fruitless. After moments of floundering, in which I gulped some of that putrid water, I was pulled “ashore.”

The best days in gym class were when we boys chose sides by counting off by twos. Number One’s became “shirts” and “Twos” skins. This replaced the grief of being the last one standing, unchosen, unwanted attention for being last. Even so, whether we chose sides by name or number, an admonition could be counted on by a teammate for me to keep out of the way if the ball came at me. Hurtful memories like this came to an end in my senior year. New York State exempted me from PE, a decision that was mandated by my committal to the bug house the summer before, from a suicide attempt.

For the rest of my days at school, I had little desire to listen, study, or learn. I was a minimalist, doing just enough to get by. A teacher remarked to my mom that I spent my time gazing out of the window. I received but hardly did I earn my high school diploma in 1967.

Dizzzylogues could rival War and Peace in terms of size with many a tale to tell, surreal—Edvard Munch-like—recollections. One such is a Beavis and Butthead moment. Two teens observed me on the ground near an amusement park ride where I had stupidly decided to get on one and wound up paying the consequences.

“Hey, mister, you having a heart attack or something?” said one.

A foot nudged me.

“Looks dead” the other said. “Or close to it.”

One of the most humiliating incidents occurred in my trying to defend the honor of a girl who had just been insulted. I made my stance known. “What are you going to do about it, Big Boy,” taunted the insulter. The would-be fistfight was over as fast as you could say “supine.”

“Pusssy,” said the victor, he and his gang laughing as they walked away. One of them kicked my ribs on the down-for-the count me for good measure. I was a pathetic, immobilized heap in the snow, a jellyfish, too sick to feel the bruise on my jaw, the kick, or the humiliation of a quick and easy out. That would come the next day.

The sight of the girl whose virtue I had deemed myself to be a chivalrous knight for, made me wish for something to cover my face or to crawl into. It was bad enough to get whipped but even more so in the presence of a girl. Surely, this incident certified me as someone who couldn’t fight his way out of a wet paper bag. Not a quality a girl admired in a boy. Even a jellyfish could do better.

My life became reclusive, and I sought to avoid circumstances to set myself up as a punching bag whether physical or by ridicule. Social outings greater than a party of one became a source of angst. Why risk embarrassing myself and putting me in a position to have to explain something I couldn’t explain?

Through the years, I kept up wishful thinking, if that’s what it was, for a cure. At least a label. I fit the definition of insanity of doing the same thing all over again expecting a different result. I hit and re-hit the doctor’s circuit.

The cardiologist in my teenage years deemed my cardiogram “normal.” The one who decades later declared me to have POTS (Postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome),a condition for fainting, but this was not my problem. I estimate, over my lifetime, I fielded a half dozen neurologists who performed brain waves, CAT scans, MRIs, nerve conduction tests, and found nothing out of the ordinary. A gastroenterologist suspected hypoglycemia. One of my psychiatrists labeled it “anticipatory anxiety.” Made up? I wondered.

Pills all over the spectrum piled on from anticonvulsants, beta-blockers, and anti-depressants, to tranquilizers. No impact, just side effects. As I got into my 50s, full-blown spells mercifully became less intense and frequent but morphed into an uptick of walking obstructions. My legs could kick out from under me. A leisurely stroll in a park with my family one evening resulted in them propping me up for the rest of the saunter home.

An encounter with a neurologist in 2018 was glum like all the others before. This time, however, luck was on my side. Indirectly, I was to hit paydirt.

“Let’s face it, Tim,” stated the neurologist, “some people are born uncoordinated.” No magic up his sleeve, no name for what I had. As a last gasp, he suggested giving a skin patch for motion sickness a whirl, an offer I declined.

Then he broke the news. He was leaving the clinic to join the faculty at a university hospital and needed to turn my case over to another neurologist, Dr. Lorraine Purino, in Arcadia, California. On my first visit, she took notes of my symptoms, explored the medical history in my family tree, and examined my gait. She Suspected episodic Ataxia, which, considering the history of stabs at a diagnosis, got me to suspect she was pulling my leg. The sound was too plain to be authentic!

Follow-up labs confirmed Episodic Ataxia, a genetic disorder of the nervous system that manifests in balance and coordination. Said to be eight types of Episodic Ataxia, my results matched Type 2 [EA2] marked by vertigo and fever, loss of balance, and difficulty speaking. Episodes can be precipitated by caffeine, alcohol, exercise, stress, and excitement. Symptoms of the disorder can be managed by medication, though I opted out since mine have lessened with age. Besides, I had no plans to try out for a basketball or football team. It was 57 years too late.

A degree of closure had come in knowing that this gatecrasher had a name. In a perverse sense, closure should contain an expression of gratitude that Episodic Ataxia may have helped me cope with life. He’s always happy; never gets mad, I had heard spoken about me. Not that I never got angry or excited, but I learned from past experiences that landed me in a state of discombobulation, on my back, slurred speech, and dealing with emotions without rocking the boat of my nervous system. I got to know myself better, like being aware of the caveats of exertion and stress and knowing my threshold; in short, to not overdo it.

In a perverse way, Episodic Ataxia may have saved my life. I had a taste for alcohol and I had a knack for daredevilry, or some would say recklessness. But the life I built around dizzy spells—or Episodic Ataxia—put a lid on this. This will be with me for my lifetime, but at least I now know after decades of ambiguity what the label is. Yes, as Dad said, it is in my head.

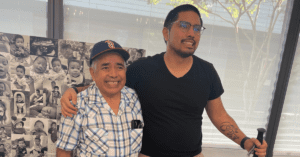

Author Bio

Tim Wahl met the challenges of Episodic Ataxia as an adult education teacher in Los Angeles, California. Retired in 2020, he recently returned from a 10-month post in Kyrgyzstan with the US State Department, where he performed ”soft diplomacy” as a guest lecturer. and speaker.